Ignacy Domejko on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ignacy Domeyko or Domejko, pseudonym: ''Żegota'' ( es, Ignacio Domeyko, ; 31 July 1802 – 23 January 1889) was a

Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2002

Ignacy Domeyko was born in the then

Ignacy Domeyko was born in the then

In 1838 Domeyko left for

In 1838 Domeyko left for

Ignotas Domeika 200

Retrieved on 2008-07-24 The term "Lithuanian" at that time designated any inhabitant, whatever his ethnicity, of the territories of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1884 Domeyko returned for an extended visit to Europe and remained there until 1889, visiting his birthplace and other places in the former Commonwealth, as well as Paris and Jerusalem. In 1887 he was awarded an

Named in honour of Domeyko are; a Cuban found genus of plants '' Domeykoa'', the mineral ''

Named in honour of Domeyko are; a Cuban found genus of plants '' Domeykoa'', the mineral ''

review

Polish language * Paz Domeyko Lea-Plaza. Ignacio Domeyko. La Vida de un Emigrante. Santiago, Chile.2002. Random House Mondadori (Editorial Sudamericana) Spanish language * Paz Domeyko. A Life in Exile. Ignacy Domeyko 1802-1889. Sydney, Australia 2005. }.9. English language. Available from author. See website Paz Domeyko, www.domeyko.org

Works of Ignacy Domeyko

in the digital library Polona. *

Memoirs of Ignacy Domeyko

*

2002 Polish conference on Ignacy Domeyko

Contains a selection of articles and book reviews, some in English * Honorata Szocik

Nasz Czas 37 (576) * Proceedings of a 2002

Ignacy Domeyko. Polymath Virtual Library, Fundación Ignacio LarramendiMuseum about Polish Explorer Being Built in Chile

{{DEFAULTSORT:Domeyko, Ignacy 1802 births 1889 deaths People from Karelichy District People from Novogrudsky Uyezd 19th-century Lithuanian nobility 19th-century Polish nobility Belarusian nobility Polish Roman Catholics 19th-century Chilean geologists Chilean geographers Chilean people of Polish descent 19th-century Polish geologists Lithuanian geologists Polish mineralogists Polish geographers Belarusian geographers Belarusian geologists Belarusian mineralogists Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Chile November Uprising participants Naturalized citizens of Chile Vilnius University alumni

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

, mineralogist

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

, educator, and founder of the University of Santiago, in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

. Domeyko spent most of his life, and died, in his adopted country, Chile.

After a youth passed in partitioned Poland

Partition may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Disk partitioning, the division of a hard disk drive

* Memory partition, a subdivision of a computer's memory, usually for use by a single job

Software

* Partition (database), the division of a ...

, Domeyko participated in the Polish–Russian War 1830–31

The November Uprising (1830–31), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in W ...

. Upon Russian victory, he was exiled, spending part of his life in France (where he had gone with a fellow Philomath

A philomath () is a lover of learning and studying. The term is from Greek (; "beloved", "loving", as in philosophy or philanthropy) and , (, ; "to learn", as in polymath). Philomathy is similar to, but distinguished from, philosophy in that ...

, Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

) before eventually settling in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, whose citizen

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

he became.

He lived some 50 years in Chile and made major contributions to the study of that country's geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

, geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

. His observations on the circumstances of poverty-stricken miners

A miner is a person who extracts ore, coal, chalk, clay, or other minerals from the earth through mining. There are two senses in which the term is used. In its narrowest sense, a miner is someone who works at the rock face; cutting, blasting, ...

and of their wealthy exploiters had a profound influence on those who would go on to shape Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

's labor movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

.

Domeyko is seen as having had close ties to several countries and thus in 2002, when UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

organized a series of commemorations of the 200th anniversary of his birth, he was referred to as "a citizen of the world".CULTURAL BULLETIN 21 (165)Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2002

Life

Early life

Russian partition

The Russian Partition ( pl, zabór rosyjski), sometimes called Russian Poland, constituted the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that were annexed by the Russian Empire in the course of late-18th-century Partitions of Po ...

of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, at Niedźwiadka Wielka

Niedźwiadka is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Stanin, within Łuków County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It lies approximately north-west of Stanin, west of Łuków, and north-west of the regional capital Lublin ...

( be, Мядзьведка, translit=Miadzviedka) Manor (Bear Cub Manor) near Nieśwież

Nesvizh, Niasviž ( be, Нясві́ж ; lt, Nesvyžius; pl, Nieśwież; russian: Не́свиж; yi, ניעסוויז; la, Nesvisium) is a city in Belarus. It is the administrative centre of the Nyasvizh District (''rajon'') of Minsk Region ...

, Minsk Governorate

The Minsk Governorate (russian: Минская губерния, Belarusian: ) or Government of Minsk was a governorate ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire. The seat was in Minsk. It was created in 1793 from the land acquired in the partition ...

, Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

(now Karelichy

Karelichy ( be, Карэлічы, Kareličy; russian: Коре́личи, ; lt, Koreličiai; pl, Korelicze; yi, קארעליץ, ''Korelitz'') is a town in the Grodno Region of Belarus and the administrative centre of Karelichy District.

The t ...

district, Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

). The Domeyko family held the Polish ''Dangiel'' coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central ele ...

. Ignacy's father, Hipolit Domeyko, who was president of the local land court ( pl, sąd ziemski), died when Ignacy was seven years old; the boy's uncles then served as his guardians.

In his youth Ignacy was a subject of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

. He had, however, been brought up in the culture of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, a multicultural state whose educated and dominant classes had spoken Polish as a ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

''. Shortly before Domeyko's birth, the Commonwealth had been dismembered in the partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for ...

. For this reason, and because Domeyko subsequently spent most of his life in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, he is considered a person of national importance to Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

, Belarusians

, native_name_lang = be

, pop = 9.5–10 million

, image =

, caption =

, popplace = 7.99 million

, region1 =

, pop1 = 600,000–768,000

, region2 =

, pop2 ...

, Lithuanians

Lithuanians ( lt, lietuviai) are a Baltic ethnic group. They are native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,378,118 people. Another million or two make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the United States, Uni ...

, and Chileans

Chileans ( es, Chilenos) are people identified with the country of Chile, whose connection may be residential, legal, historical, ethnic, or cultural. For most Chileans, several or all of these connections exist and are collectively the source ...

.

Domeyko enrolled at Vilnius University

Vilnius University ( lt, Vilniaus universitetas) is a public research university, oldest in the Baltic states and in Northern Europe outside the United Kingdom (or 6th overall following foundations of Oxford, Cambridge, St. Andrews, Glasgow and ...

, then known as the Imperial University of Vilna, in 1816 as a student of mathematics and physics. He studied under Jędrzej Śniadecki

Jędrzej Śniadecki (archaic ''Andrew Sniadecki''; ; 30 November 1768 – 11 May 1838) was a Polish writer, physician, chemist, biologist and philosopher. His achievements include being the first person who linked rickets to lack of sunlight. He ...

. Involved with the Philomaths

The Philomaths, or Philomath Society ( pl, Filomaci or ''Towarzystwo Filomatów''; from the Greek φιλομαθεῖς "lovers of knowledge"), was a secret student organization that existed from 1817 to 1823 at the Imperial University of Vilniu ...

, a secret student organisation dedicated to Polish culture and the restoration of Poland's independence, he was a close friend of Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

. In 1823–24, during the investigation and trials of the Philomaths, Domeyko and Mickiewicz spent months incarcerated at Vilnius' Uniate Basilian monastery.

After participating in the November 1830 Uprising, in which Domeyko served as an officer under General Dezydery Chłapowski

Baron Dezydery Adam Chłapowski (1788 in Turew – 27 March 1879) of the Dryja coat of arms was a Polish general, businessman and political activist.

Early life

His father Józef Chłapowski (born 1756, died 1826) was the baron of Kościan Co ...

, in 1831 Domeyko was forced into exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

in order not to face Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

n reprisals.

Exile

Journeying through Germany, he arrived in France, where he would earn an engineering degree at Paris' ''École des Mines

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education

Secondary education or post-primary education covers two phases on the International Standard Classification of Education scal ...

'' (School of Mining). He also studied at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

and maintained his political engagements with Belarusians, Poles, and Lithuanians.

Chile

In 1838 Domeyko left for

In 1838 Domeyko left for Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

. There he made substantial contributions to mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

and the technology of mining, studied several previously unknown minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

, advocated for the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

of the native tribal peoples, and was a meteorologist

A meteorologist is a scientist who studies and works in the field of meteorology aiming to understand or predict Earth's atmospheric phenomena including the weather. Those who study meteorological phenomena are meteorologists in research, while t ...

and ethnographer

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

. He is also credited with introducing the metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that succeeded the Decimal, decimalised system based on the metre that had been introduced in French Revolution, France in the 1790s. The historical development of these systems culminated in the d ...

to Latin America.

He served as a professor at a mining college in Coquimbo

Coquimbo is a port city, commune and capital of the Elqui Province, located on the Pan-American Highway, in the Coquimbo Region of Chile. Coquimbo is situated in a valley south of La Serena, with which it forms Greater La Serena with more than ...

( La Serena) and after 1847 at the University of Chile

The University of Chile ( es, Universidad de Chile) is a public research university in Santiago, Chile. It was founded on November 19, 1842, and inaugurated on September 17, 1843.

(''Universidad de Chile'', in Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose ...

), of which he was rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

for 16 years (1867–83).

Domeyko gained Chilean citizenship in 1849, but declared at the time that "I may now never change my citizenship, but God grants me hope that wherever I may be—whether in the Cordillera

A cordillera is an extensive chain and/or network system of mountain ranges, such as those in the west coast of the Americas. The term is borrowed from Spanish, where the word comes from , a diminutive of ('rope').

The term is most commonly us ...

s or in he_Vilnius_suburb_of.html"_;"title="Vilnius.html"_;"title="he_Vilnius">he_Vilnius_suburb_of">Vilnius.html"_;"title="he_Vilnius">he_Vilnius_suburb_ofPaneriai.html" ;"title="Vilnius">he_Vilnius_suburb_of.html" ;"title="Vilnius.html" ;"title="he Vilnius">he Vilnius suburb of">Vilnius.html" ;"title="he Vilnius">he Vilnius suburb ofPaneriai">Vilnius">he_Vilnius_suburb_of.html" ;"title="Vilnius.html" ;"title="he Vilnius">he Vilnius suburb of">Vilnius.html" ;"title="he Vilnius">he Vilnius suburb ofPaneriai—I shall die a Lithuanian."UNESCOIgnotas Domeika 200

Retrieved on 2008-07-24 The term "Lithuanian" at that time designated any inhabitant, whatever his ethnicity, of the territories of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1884 Domeyko returned for an extended visit to Europe and remained there until 1889, visiting his birthplace and other places in the former Commonwealth, as well as Paris and Jerusalem. In 1887 he was awarded an

honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

by the Jagiellonian University

The Jagiellonian University (Polish: ''Uniwersytet Jagielloński'', UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and the 13th oldest university in ...

, in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

.

In 1889, soon after returning to Santiago, Chile, Domeyko died.

Memorials

domeykite

Domeykite is a copper arsenide mineral, Cu3As. It crystallizes in the isometric system, although crystals are very rare. It typically forms as irregular masses or botryoidal forms. It is an opaque, white to gray (weathers brassy) metallic minera ...

'', the shellfish '' Nautilus domeykus'', the genus of dinosaur '' Domeykosaurus'', the ammonite '' Amonites domeykanus'', asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere.

...

'' 2784 Domeyko'', the ''Cordillera Domeyko

The Cordillera Domeyko is a mountain range of the Andes located in northern Chile, west of Salar de Atacama. It runs north-south for approximately 600 km, parallel to the main chain. The mountain range marks the eastern border of the flat pa ...

'' mountain range in the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

, and the Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

an town of '' Domeyko''.

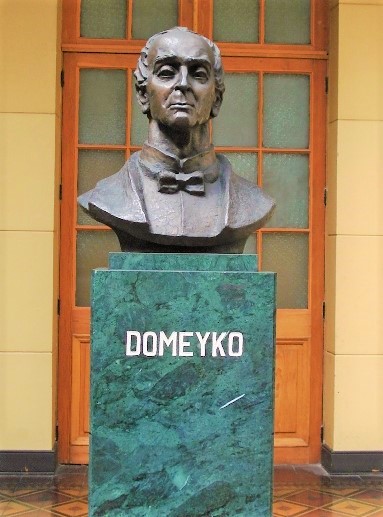

A bronze bust of Domeyko stands in the Casa Central de la Universidad de Chile

The Casa Central de la Universidad de Chile, also known as ''Palacio de la Universidad de Chile'', is the main building for the Universidad de Chile, and is located at 1058 Alameda Libertador Bernardo O'Higgins, in Santiago, Chile. The building d ...

, of which Domeyko was long-time rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

.

In 1992, a plaque in Spanish and Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

was placed on a building at '' Krakowskie Przedmieście 64'', in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, Poland, commemorating the "distinguished son of the Polish nation and eminent citizen of Chile."

On the 200th anniversary of his birth, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

declared 2002 to be "Ignacy Domeyko Year." Several commemorative events were held in Chile under the auspices of Polish President Aleksander Kwaśniewski

Aleksander Kwaśniewski (; born 15 November 1954) is a Polish politician and journalist. He served as the President of Poland from 1995 to 2005. He was born in Białogard, and during communist rule, he was active in the Socialist Union of Poli ...

and Chilean President Ricardo Lagos

Ricardo Froilán Lagos Escobar (; born 2 March 1938) is a Chilean lawyer, economist and social-democratic politician who served as president of Chile from 2000 to 2006. During the 1980s he was a well-known opponent of the Chilean military di ...

.

In 2002, Poland and Chile jointly issued a postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the fa ...

commemorating the 200th anniversary of Domeyko's birth.

Also in 2002, a 200th-birthday plaque honoring him was placed in the entry gate to Uniate

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of th ...

Basilian monastery

Basilian monks are Roman Catholic monks who follow the rule of Basil the Great, bishop of Caesarea (330–379). The term 'Basilian' is typically used only in the Catholic Church to distinguish Greek Catholic monks from other forms of monastic li ...

in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

, Lithuania, where he and Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

were held in 1823–24 during the investigation and trials of the Philomaths

The Philomaths, or Philomath Society ( pl, Filomaci or ''Towarzystwo Filomatów''; from the Greek φιλομαθεῖς "lovers of knowledge"), was a secret student organization that existed from 1817 to 1823 at the Imperial University of Vilniu ...

.

In 2015 a Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

ian climber Pavel Gorbunov placed a memorial plate on the top of Cerro Kimal in Cordillera Domeyko

The Cordillera Domeyko is a mountain range of the Andes located in northern Chile, west of Salar de Atacama. It runs north-south for approximately 600 km, parallel to the main chain. The mountain range marks the eastern border of the flat pa ...

.

Notes

See also

* Biblioteca Polaca Ignacio Domeyko *Polish-Lithuanian (adjective)

The Polish-Lithuanian identity describes individuals and groups with histories in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth or with close connections to its culture. This federation, formally established by the 1569 Union of Lublin between the Kingdo ...

*List of minor planets named after people

This is a list of minor planets named after people, both real and fictional.

Science

Astronomers

Amateur

*340 Eduarda (Heinrich Eduard von Lade, German)

* 792 Metcalfia (Joel Hastings Metcalf, American)

*828 Lindemannia (Adolph Friedrich Lindem ...

*List of Poles

This is a partial list of notable Polish or Polish-speaking or -writing people. People of partial Polish heritage have their respective ancestries credited.

Science

Physics

* Czesław Białobrzeski

* Andrzej Buras

* Georges Charpak ...

References

* Polish language * Polish language * Polish language * Polish language * Portuguese language *review

Polish language * Paz Domeyko Lea-Plaza. Ignacio Domeyko. La Vida de un Emigrante. Santiago, Chile.2002. Random House Mondadori (Editorial Sudamericana) Spanish language * Paz Domeyko. A Life in Exile. Ignacy Domeyko 1802-1889. Sydney, Australia 2005. }.9. English language. Available from author. See website Paz Domeyko, www.domeyko.org

External links

Works of Ignacy Domeyko

in the digital library Polona. *

Memoirs of Ignacy Domeyko

*

2002 Polish conference on Ignacy Domeyko

Contains a selection of articles and book reviews, some in English * Honorata Szocik

Nasz Czas 37 (576) * Proceedings of a 2002

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

ian conference about Domeyko.Ignacy Domeyko. Polymath Virtual Library, Fundación Ignacio Larramendi

{{DEFAULTSORT:Domeyko, Ignacy 1802 births 1889 deaths People from Karelichy District People from Novogrudsky Uyezd 19th-century Lithuanian nobility 19th-century Polish nobility Belarusian nobility Polish Roman Catholics 19th-century Chilean geologists Chilean geographers Chilean people of Polish descent 19th-century Polish geologists Lithuanian geologists Polish mineralogists Polish geographers Belarusian geographers Belarusian geologists Belarusian mineralogists Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Chile November Uprising participants Naturalized citizens of Chile Vilnius University alumni